This entry is part of the Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks Writing Challenge – Week 47: Soldier

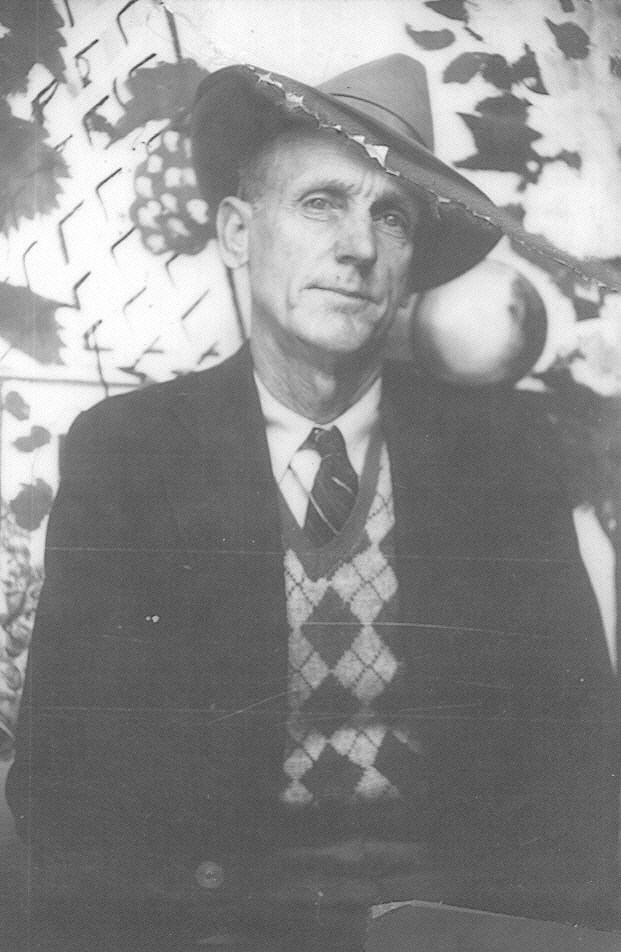

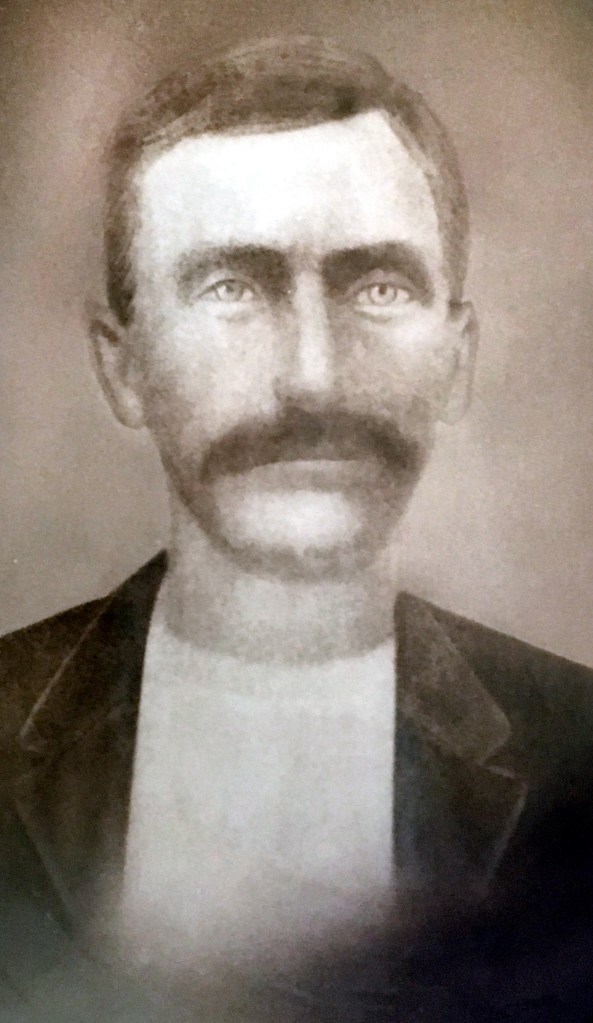

I love being able to see photographs of my ancestors. This is the only photo I have ever seen of my great- great grandfather, William Andrew Roundtree. As I look at his face, I sense that he was perhaps a solemn person with much weighing on his mind. When I look back at the records, that is my only insight into his life, I am able to piece together his story; a story not without burdens, sorrow and hardships. As a young man, he was a soldier during the Civil War. I can picture him in his Confederate uniform and cap as I try to imagine what his life as a soldier might have been like at such a young age.

William Andrew Roundtree, son of James Woodson Roundtree and Mary Elizabeth Burns[1], was born in Arkansas in 1844[2]. His family moved to Texas around 1851 when William was about seven years old. [3] They first settled in Shelby County, Texas and then Hardin County, Texas where many Roundtree descendants still live. It was in Hardin County where, at the age of seventeen, William Andrew Roundtree first volunteered for military service and in 1862, enlisted in the 1st Texas Regiment, Company F.[4]

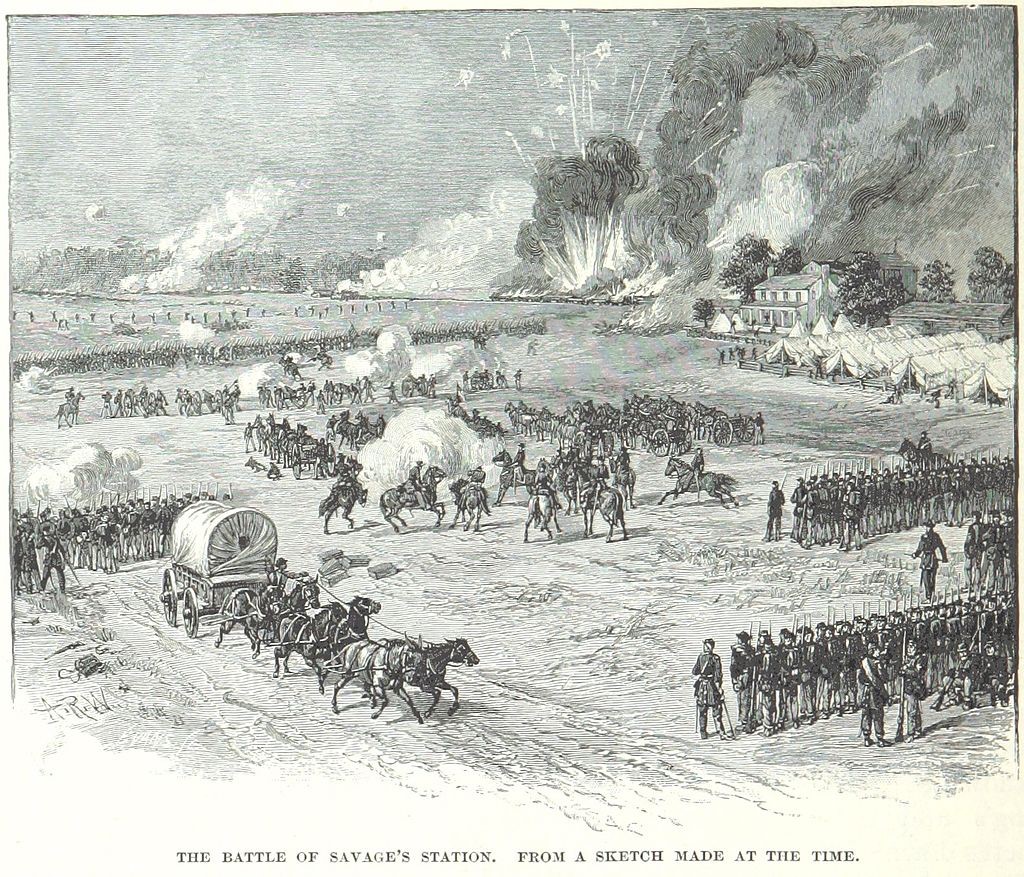

It wasn’t long before William saw his first battle. On June 29, 1862, the Texas 1st was engaged in battle at The Battle of Savage’s Station in Henrico County, Virginia.[5]

“The battle began around nine o’clock in the morning and went on throughout the day reaching a bloody stalemate as darkness fell and strong thunderstorms began to move in leaving approximately 1500 wounded men on each side”.[7] William Andrew Roundtree suffered no known wounds from this battle, though being only eighteen years old, I can imagine he suffered anguish and anxiety having witnessed and participated in such an event. For the next year, he participated in a variety of other engagements and was present for all his company’s muster rolls.[8]

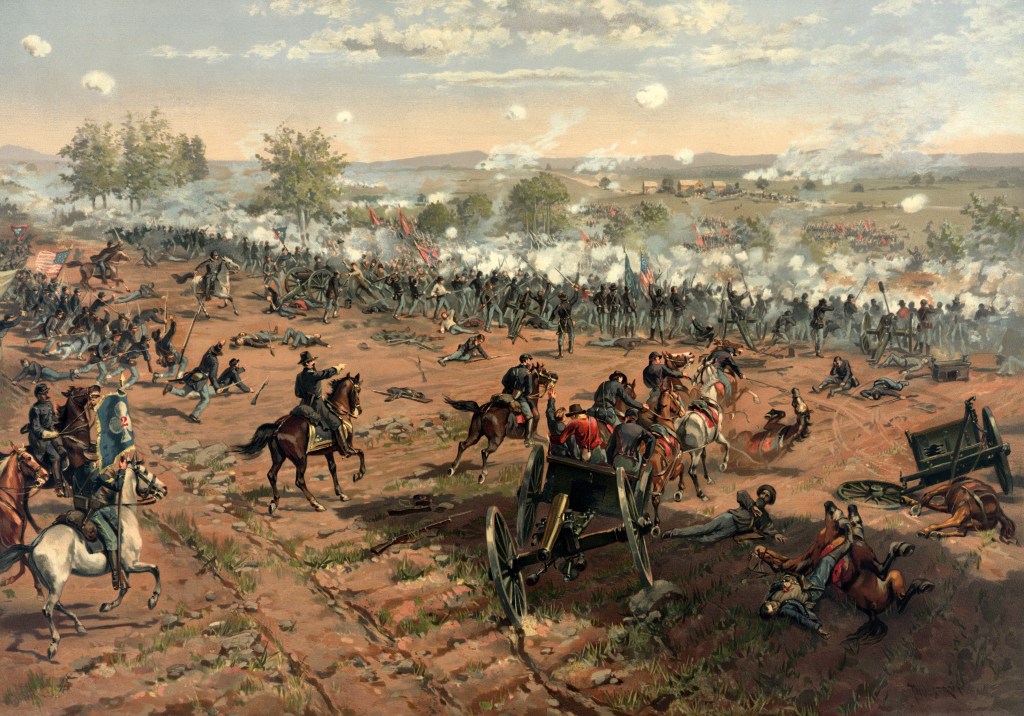

The battle that not only changed the tide of the war, but also the life of my ancestor, happened in the first few days of July 1863; it was called The Battle of Gettysburg. On the second day of battle, July 2, 1863, William Roundtree was wounded.[9] Both armies suffered extremely heavy losses on July 2, with 9,000 or more casualties on each side. The combined casualty total from two days of fighting came to nearly 35,000, the largest two-day toll of the war.[10]

William was eventually taken to the Wayside Hospital in Richmond, Virginia and is shown on the register as being admitted on July 20, 1863.[12] He remained in the hospital for quite some time and appears on a register of the General Hospital, Howard’s Grove, Richmond, Virginia on November 13, 1863. It was during his stay at this hospital that he had his right hand amputated.[13] “With so many patients, doctors did not have time to do tedious surgical repairs, and many wounds that could be treated easily today became very infected. So, the army medics amputated lots of arms and legs, or limbs. About three-fourths of the operations performed during the war were amputations. These amputations were done by cutting off the limb quickly in a circular sawing motion to keep the patient from dying of shock and pain. Remarkably, the resulting blood loss rarely caused death. Surgeons often left amputations to heal by granulation. This is a natural process by which new capillaries and thick tissue form much like a scab to protect the wound. When they had more time, surgeons might use the “fish-mouth” method. They would cut skin flaps (which looked like a fish’s mouth) and sew them to form a rounded stump.”[14]

American Civil – War era amputation and surgical set

William was transferred to Chimborazo Hospital (also in Richmond, Virginia) on January 29, 1864 to complete his recovery time. He remained at Chimborazo until June 1864 when he was retired by the Medical Examining Board as “unfit for service”[16]. I feel that he had integrity and a little spunk and determination, for within that same month, William Andrew Roundtree registered for the Invalid Corps at the military station in Beaumont, Texas.[17] The Invalid Corps was organized to give cripple or partially crippled soldiers the opportunity to remain a part of the military doing useful but simple work while freeing up able bodied men to fight on the front.

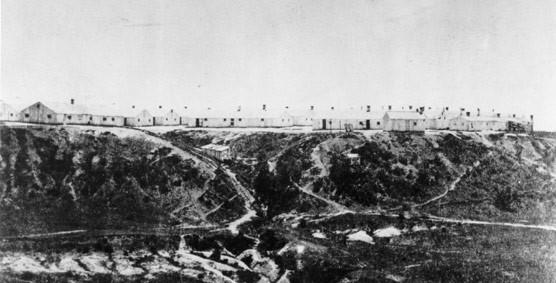

Chimborazo Hospital, the “hospital on the hill.” Considered the “one of the largest, best-organized, and most sophisticated hospitals in the Confederacy.” Library of Congress

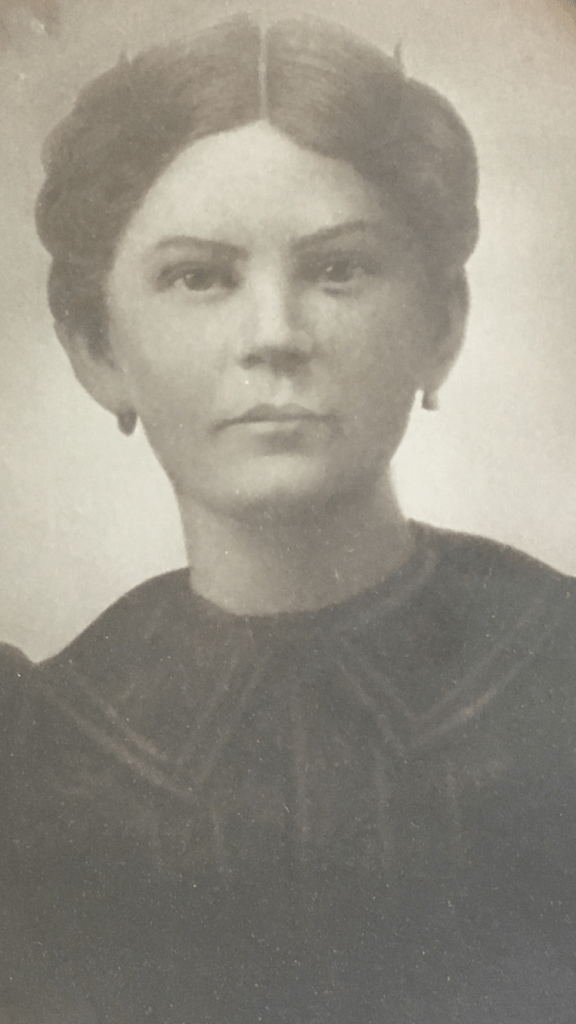

After the war, William returned home to Hardin County and married Mary Durham, a widowed woman with two small children.[18] Together, William and Mary had one child, a son, Robert Lee Roundtree who was born on June 26, 1866.[19] It’s hard for me to imagine what a life of a farmer would have been like having the use of only one of his hands. His wife, I’m sure, worked the farm as well pulling together to make a life. It wasn’t to last long however, as sometime between 1870 and 1872, she passed away from unknown reasons.

Mary (maiden name unknown) Durham Roundtree – First wife of William Andrew Roundtree

William remarried on November 14, 1872 to Georgianna May McClendon.[20] In 1876, William moved his family to Limestone County.

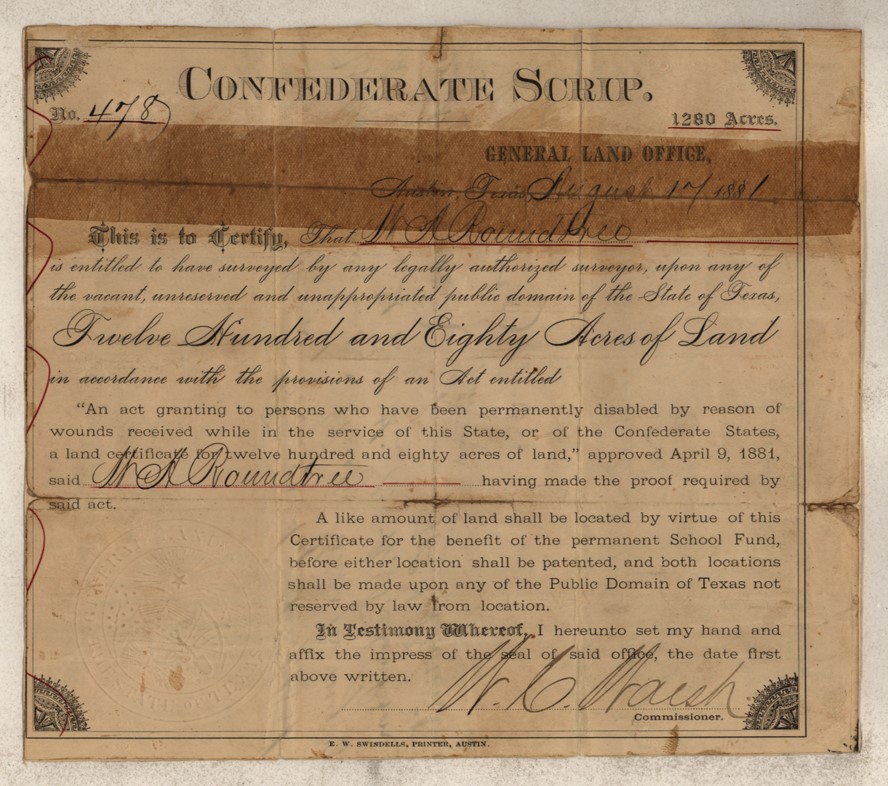

He received a Confederate Script in 1881 which entitled him to 1, 280 acres of land. This script of land was located in Red River County. [21]

Shortly after receiving his Confederate Script, William Andrew Roundtree purchased 183 ½ acres of land in Limestone County[22]. There has been speculation in the family and even a court case arguing whether William sold his script of land. That in itself is enough for an entire story on its own. After thoroughly examining the documents and other sources, it is my opinion, that William was able to purchase the land in Limestone County with the proceeds of the sale of the Script. He is listed in the tax rolls each proceeding year through 1887 as having the 183 ½ acres of land. In the 1888 tax rolls for Limestone County, William is listed as having only forty acres of land. This is shown each year until his death in 1899. More research is needed to determine what happened to this property as I have not been able to locate any type of deed record.

William Andrew Roundtree and Georgianna May McClendon had the following children; Minnie Lee Roundtree was born in 1873, Mollie 1876, Willie 1877, Nancy Josephine 1879, Jesse James 1885, Virginia “Jennie” 1890, Andrew Lawrence (my great grandfather) 1891, Woodson 1892 and Melvin Lenard 1895.

Georgianna May McClendon Roundtree with four of her children; L to R: Melvin, Leonard, Woodson and Virginia

(Photo was taken shortly after the death of William Andrew Roundtree)

William is buried in an unmarked grave in Hogan Cemetery in Limestone County, Texas. He is buried next to his father, James Woodson Roundtree. It is my hope to have his grave marked with a headstone in the near future.

[1] DNA analysis using the Ancestry test results from various documented descendants of James Woodson Roundtree and Mary Elizabeth Burns compared to documented descendants of William Andrew Roundtree, in combination with circumstantial evidence and indirect sources; Analysis performed by Teresa Penny 2019; In possession of Teresa Penny

[2] 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration; Ancestry.com, Provo, UT

[3]1867 Voter Registration Lists. Microfilm, 12 rolls. Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, Texas. Ancestry.com. Texas, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

[4] National Park Service U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865

Provo, UT, USA; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2007. Original data National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Systems

[5] ibid

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Savage%27s_Station

[7] ibid

[8] National Park Service U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865

Provo, UT, USA; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2007. Original data National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Systems

[9] ibid

[10] https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/battle-of-gettysburg

[11] https://www.goodfreephotos.com/historical-battles/american-civil-war/the-battle-of-gettysburg-painting-american-civil-war.jpg.php

[12] National Park Service U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 [database online] Provo, UT, USA; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2007. Original data National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Systems

[13] ibid

[14] https://www.ncpedia.org/history/cw-1900/amputations

[15] ibid

[16] National Park Service U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 [database online] Provo, UT, USA; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2007. Original data National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Systems

[17] ibid

[18] 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc.2009, Provo, UT, USA

[19] U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current; Ancestry.com; 2012; Provo, UT, USA

[20] Louisiana, Marriages, 1718-1925; Compiled from a variety of sources including original marriage records located in Family History Library microfilm, microfiche, or books. Original marriage records are available from the Clerk of the Court where the marriage license was issued. Ancestry.com Operations Inc.; 2004, Provo, UT, USA

[21] http://www.glo.texas.gov/ncu/SCANDOCS/archives_webfiles/arcmaps/webfiles/landgrants/PDFs/3/3/3/333346.pdf

[22] Limestone County Tax Rolls; Abstract #21 M.R. Palacious; 183 ½ acres; Microfilm Collection; Groesbeck Public Library; Groesbeck, Texas